Sue William Silverman (http://www.

Silverman’s second memoir, Love Sick: One Woman’s Journey through Sexual Addiction (W.W. Norton & Company, 2008) was made into a Lifetime TV Original Movie, starring dancer and actress, Sally Pressman, who currently appears on the Lifetime Television series, Army Wives.

As a professional speaker and writer, Silverman has appeared on many nationally syndicated radio and TV programs, including The View and Anderson Cooper on CNN. She will be moderating a panel at the 2012 annual AWP Conference in Chicago about Shifting Voices in Fiction and Creative Nonfiction, with panelists Connie May Fowler, Xu Xi, Robert Vivian, and Philip Graham.

Silverman teaches in the low-residency MFA in Writing Program at Vermont College of Fine Arts, and lives in Michigan with her partner, poet Marc Sheehan,

and their two cats.

Derek Alger: How’s the world look from western Michigan these days?

Sue William Silverman: These long, winter days are bleak and gray. All winter I wait for summer. I grew up in the West Indies, and I still feel like an islander! But I live only five blocks from Lake Michigan, and it’s gorgeous here in the warm months. So, really, I shouldn’t complain.

I live in a small town, without much to do. Which is fine with me. I have lots of time to write and work with my students. I teach in the MFA in Writing program at Vermont College of Fine Arts. It’s a low-residency program, which means we go to campus twice a year, ten days each, at the beginning and end of the semester, for intensive workshops, lectures, and readings. Then, the rest of the semester, I work from home, long-distance, with five students who live all over the country. Once a month they send me their writing to be critiqued. I love to teach in this way. Working with only five students, I’m able to give them an enormous amount of personal attention. It’s gratifying to watch their writing grow and evolve over the semester.

DA: You were a writer before you ever started writing.

SWS: Yes! I hoarded words in my mind. I envisioned scenes in my head. But for years I lacked the self-confidence to actually place these words on pieces of paper. I think it comes from growing up in my incestuous family, where language was all upside down. I could never speak my truth, the truth of this dark, destructive relationship I had with my father. For example, since my father showed his love sexually, I didn’t know the difference between “love” and “sex” – the words or the feelings associated with them. After all, my father told me he loved me when he sexually molested me.

Language, as well as definitions for words, was confusing, so, for years, I was very tentative about actually committing a word to paper.

DA: Tell us about the changing geographical spheres of your childhood.

SWS: I was born in Washington, D. C., where my father was chief counsel of Trust Territories in the Department of the Interior. Then, when I was in second grade, my family moved to St. Thomas, where my father opened a bank. We left the island when I was in seventh grade, moving to suburban New Jersey. And, after that, I’ve moved around quite a bit: Boston, back to Washington, D. C., Texas, Missouri, Georgia. Now Michigan.

So I don’t really have a sense of home. Or one home.

Every place I’ve lived has influenced my writing. When I write about St. Thomas, for example, I tend to have a very specific Caribbean vocabulary – which is different, say, from writing about New Jersey, with my New Jersey vocabulary – if that makes sense! As I set any given piece of writing in a particular place I’ve lived, each has its own scents and sounds, so this affects the imagery I use, the vocabulary I “taste.”

DA: Your family moved to New Jersey where you graduated from high school.

SWS: Moving away from the West Indies was culture shock, for sure. I was a teenager then and I just wanted to fit in. But I arrived at Glen Rock High School in my madras clothes and tanned skin. I looked so different from the other students. I sounded different, too, as I’d picked up a bit of a West Indian accent.

But I set out to fit in as quickly as possible. I made friends. I acted like everyone else. Now, looking back on it, I was, ironically, probably more interesting as a Caribbean girl! But what do teenagers know?

DA: I know as a teen I thought I knew much more than I really did.

SWS: I never felt as if Glen Rock was home – any more than any other place I’ve lived. To me, in many ways, the only sense of home I have are the words and memories in my head. Home is the color of frangipani flowers in the Caribbean; the scent of crimson leaves in autumn New Jersey; the red brick of Back Bay Boston, where I went to college, and so on.

DA: Did you feel pressured or was attending college a given.

SWS: My family thought education was very important. It was assumed I’d go to college. At the same time, my mother told me that I had to go to college to meet a husband. How antiquated does that sound? And I didn’t meet my husband in college!

But I had no mentors growing up, or anyone guiding me about what to major in – nothing like that. On a positive note, summers, in college, I worked on Capitol Hill as an intern. I loved that. After graduation, I returned to Capitol Hill to work for a few years as a legislative and administrative aide.

DA: You gained valuable experience writing.

SWS: Yes. It’s kind of ironic. While working on Capitol Hill I did a lot of writing: I wrote speeches and inserts for the Congressional Record for various politicians. I wrote in their voices. I guess I had to do that before I finally learned to write in my own voice.

DA: A turning point was moving to Galveston.

SWS: Yes. After marrying a man I met in D. C., we moved when he got a job as director of the Galveston Historical Foundation.

This is where I started to write. It may be that Galveston reminded me of St. Thomas – a tropical island – which set off a sensory chain reaction. One day, seemingly out of nowhere, I set up a card table in the guest room in our apartment, put a Smith-Corona portable typewriter on it, bought a sheaf of canary- yellow typing paper, sat down, and began. At that point, I would call it more typing than writing. But I produced about one thousand pages before I realized I didn’t know how to write! So I took an adult education class at the University of Houston.

No one was talking about memoir or creative nonfiction back then, so I set out to write a novel. Thank goodness it was never published. I actually ended up with about four or five bad novels. They were mainly about incestuous relationships and alienated teenage girls. Yet even though these novels lacked an emotionally authentic voice, still, over time, I did learn how to write. I was just in the wrong genre. I didn’t find my authentic voice as a writer until I switched to creative nonfiction, years later.

DA: You paid your dues going your own apprenticeship as a writer learning the craft.

SWS: I did. With every word I wrote I was getting closer to my true writing self, which finally emerged in my two memoirs.

DA: You were forced to live a traumatic double life as a child, one veiled in deep secrecy.

SWS: Yes. Even though, growing up, I lived in this incestuous family, no one ever talked about it. I don’t even ever remember hearing the word “incest” until college.

Throughout my childhood, I lived a double life: on the surface, we seemed like a perfect family. But that was a mask that hid the secret of what my father did to me in private. That was my reality. So, in one sense, it even seemed normal. That’s how strong denial is. I just remember feeling numb most of the time. I watched how other girls acted, and mimicked them.

Later, there was much shame and confusion and anger. How could a father who said he loved me have hurt me? And there was anger toward my mother for not protecting me. It took many years of therapy to process all of this!

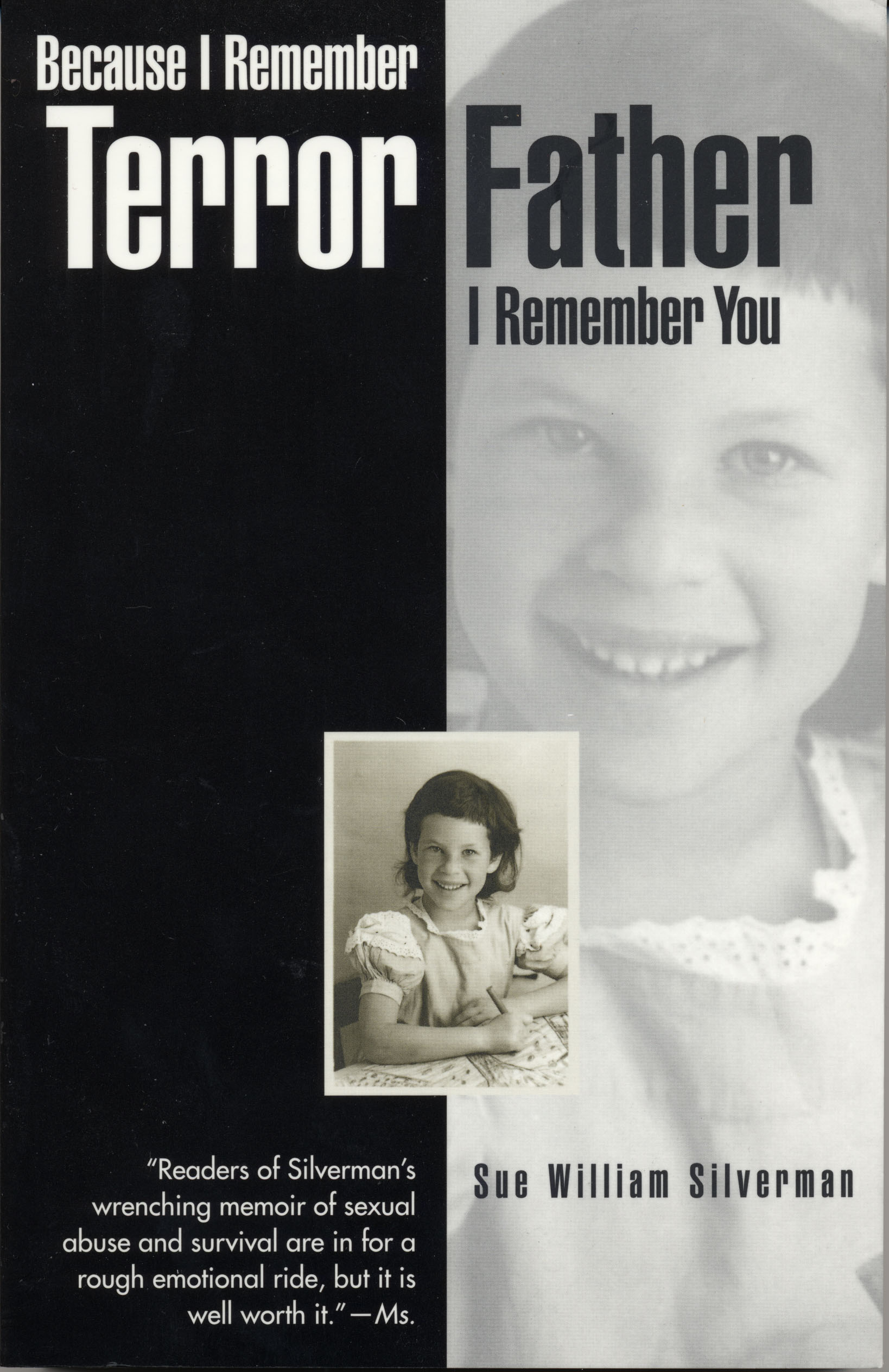

DA: You captured this horrific experience in your memoir, Because I Remember Terror, Father, I Remember You.

SWS: I began that memoir two weeks after my parents died, within six days of each other, and at the urging of my therapist, who suggested I stop writing fiction and tell my true story. He was the first person to hear the real “me.” To be honest, at that point, I’d never even read a memoir…except for The Diary of Anne Frank. Anyway, I sat down at my computer, and, in three months, Because I Remember Terror, Father, I Remember You just “fell” out of me.

While writing that book, I never thought about how it might be perceived, what family or friends might think, or even about possible publication. I totally shut out the world. At that point in the process, all that mattered was getting the words down on the page.

To write memoir is to understand and make sense of experience, to give a life an organization, to discover the metaphors of one’s narrative. It’s not simply to say, “this happened to me, then this happened to me, then this next thing happened to me.” “What happened” is part of it. But it’s much more interesting to discover the story behind the story – what you could never have known at the time of the events – but what you (the author) discover about those events now by reflecting upon them. So, for example, in “Because I Remember Terror…,” I learned how growing up without a true language, or voice, affected me.

DA: Your memoir won the annual AWP Award for creative nonfiction.

SWS: I was shocked. The odd thing about winning a literary award and getting published is that you are still the same writer, the same person as before this public recognition. But the world perceives you differently.

All of a sudden people saw me as a writer! Which is lovely, don’t get me wrong. And publishing the book opened up many opportunities. But, inside, I’m still the same person I was before I got published. Well, okay, maybe I have a bit more self–confidence!

DA: You tackled a difficult subject in your second memoir, Love Sick: One Woman’s Journey through Sexual Addiction, an issue that is minimized by many.

SWS: That was a tough book to write.

First, on a personal level, I had much more shame about struggling with sex addiction than being an incest survivor. Yes, the addiction was a result of the childhood incest – since my father saw me as a sex object, that’s how I saw myself – and, I thought that’s the only way any man would see me. Still, it’s difficult to convey sympathy for an adult woman having affairs with married, emotionally dangerous men.

In the writing of the book, this was my challenge and my struggle: Initially, I found it difficult to discover an emotionally authentic voice to convey the whole of the experience. In early drafts, I only heard the voice of the addict – that tough, edgy persona. But with just that addict voice, it was one-dimensional – how boring to read only about the unenlightened life of a sex addict. It was like I lopped off half of my experience. It took about five years to hear the voice of the woman struggling to get sober. While the book itself is a weaving together of these two voices, still, the sober voice is at the heart of Love Sick. And finally it all coalesced.

DA: You also are the author of Fearless Confession: A Writer’s Guide to Memoir.

SWS: I think of Fearless Confessions as a guidebook for people who want to take possession of their lives by putting their experiences down on paper.

I wanted the book to sound friendly, inviting, intimate: we’re all writers, we’re all in this together. It became, in part, a memoir about my writing journey. However, there is plenty of craft information in it, too, chapters about metaphor, voice, structure, the use of sensory detail. It contains many writing exercises that help writers navigate a range of issues from craft to ethics to marketing. I also have a chapter about the importance of memoir, and how memoir is as legitimate a genre as poetry and fiction – just taking on all the naysayers out there who call us navel gazers!

DA: You’ve also published a poetry collection, Hieroglyphics in Neon.

SWS: After I finished the two memoirs, I needed to write something very different. And, since my partner, Marc Sheehan, is a poet, he suggested I try poetry. Well, at first this was scary. Line breaks terrified me. I’d never even written bad high-school poetry. But Marc was a great teacher. And he helped me overcome my fear of line breaks.

Writing this collection turned out to be a truly joyful – freeing – experience. I mean, you can’t really say that writing about incest and sex addiction is going to be joyful! One thing I love about poetry is the ability to “time travel” without having to get people in and out of doors as you do in prose. Plus, I could pretend, say, to be Queen Hatasu, an Egyptian pharaoh. I loved writing persona poems.

DA: What’s on the horizon?

SWS: I just finished writing what I call a cultural memoir, The Pat Boone Fan Club: My Life as a White Anglo-Saxon Jew. Through a series of linked essays, the manuscript chronicles my search for authentic self-identity – a search complicated by my conflicted feelings toward Judaism and my various efforts to “pass” as Christian. (I wanted to be Christian since my Jewish father sexually molested me.) At the heart of this journey are three separate encounters with 1960s pop-music icon, turned Christian provocateur, Pat Boone, who plays a pivotal role in my desire to belong to the dominant culture.

This book has a much more ironic voice than the voice(s) of my previous books. My first memoir is written in the voice of a young, scared child trying to survive her childhood. Then, in Love Sick, there’s the voice of the addict as well as the more sober voice. In this new book, as I say, I implement an ironic tone as I try to come to terms with my religion.

That’s one thing I love about creative nonfiction: there are endless ways to discover new voices and additional stories. We already have these different identities, so as writers we need only discover the various voices in order to explore them on the page.

Until I discover the voice to examine events, they remain murky – blending and bleeding together. It is only by writing that I am fully able to understand these identities and make sense of my whole life.