Ani Gjika was born and raised in Albania, before moving to the United States with her parents at the age of 18 and studying poetry at Simmons College and Boston University.

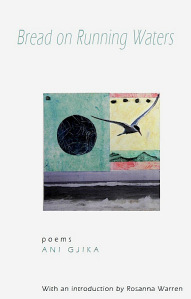

Her poetry collection, Bread on Running Waters, published by Fenway Press (http://www.fenwaypress.com), was a finalist for the 2011 Anthony Hecht Poetry Prize and 2011 May Sarton New Hampshire Book Prize.

Gjika is also the recipient of a 2010 Robert Pinsky Global Fellowship and was the winner of a 2010 Robert Fitzgerald Translation Prize. She teaches at Massachusetts International Academy, and is currently working on an anthology of poetry in translation by Albanian women.

Derek Alger: I find it amazing English is your second language, especially after reading your poetry.

Ani Gjika: Thank you, Derek. But I honestly feel that I live in the realm of the semi-inarticulate. I left my home country of Albania when I was 18 to move to the United States. I studied some English when I was eight years old back in Albania, but didn’t really learn to speak the language until after moving here and taking up an English major in the late ‘90s. Since then, English has become my first language and yet, I am aware of how limited my English lexicon is. And the same is true of my Albanian lexicon. I feel like I have one foot in each language, far apart from each other, and therefore never able to stand up straight.

DA: Your parents were a strong influence on you.

AG: They were and still are. If it weren’t for them, I would have probably never gotten into languages so early in my life. They arranged for me to study English and Italian with a private tutor and then later, major in Russian in high school. Very few people took Russian in high school back then. English and German were the popular foreign languages. And even though I felt like my parents were dictating this choice for me, I immediately loved Russian and I had the sense that if I didn’t, they would have allowed me the option to switch to something else.

We lived in a 650 sq. ft. apartment for the first 18 years of my life, but we owned a decent number of books. My earliest memories are of my parents being at work, my grandmother sitting on her bed reading her Bible and me sitting on the floor in the living room browsing through these heavy, chocolate colored, hard-cover Encyclopedias of Russian Literature. The books were filled with lots of what seemed to me magical, black and white illustrations. Thank god for Google, here’s a picture of one of them: http://minsk.mn.slando.by/obyavlenie/kratkaya-literaturnaya-entsiklopediya-kle-ID4ehtl.html

There were also smaller books two of which I remember vividly because they had a soft green cover, the text inside was arranged differently, and they were written by strangely named authors or had strange titles like Gitanjali (years later I made the connection to Tagore) and Walt Whitman (the “w” is not a letter in the Albanian alphabet). There was also my mother’s own first book of poetry on the cover of which I drew circles because I knew it was hers and in my head I think I was simply claiming it, not destroying it. My father, who was a professor of Albanian linguistics and did a lot of research and writing in the city’s main library, would often bring home books from there. Albanian and Greek myths and legends were my favorites. I remember I couldn’t wait to finish reading Aeschylus so I could start over again.

DA: What was your early schooling like?

AG: It felt pretty regimented. I remember having to show up early and line up in the courtyard, go through the physical exercise routine, then sing some sort of hymn to the Communist Party or Enver Hoxha and finally go inside to my classes. The whole uniformity of it all used to make me very nervous. We had to follow strict moves, sing specific songs at a specific pitch, wear uniforms. But it was also a simpler time that seems like forever ago. I lived in the capital city and went to good schools, but there was no central heating in our classrooms. Sometimes the glass was broken on the windows and replaced with plastic wrap. We had a very small wood stove in the center of each classroom and that was supposed to heat the entire room. Everyone kept their jackets on in the winter. And at lunch time, I loved toasting bread on top of that stove taking turns with my classmates. Sometimes our teacher wouldn’t go to the teachers’ office, but stay back and have plain toast and butter with us. Really, sounds like such an innocent world from centuries ago. I haven’t even thought of this until now. Geez.

Around the end of my first grade, in April 1985, Enver Hoxha, who had been Albania’s Communist leader since 1944, died. I remember vividly how some teachers gathered a couple of the classes and took us all on a walk to a field nearby. And there they told us. But they were crying and shaking and then my classmates started crying and I felt really weird, like they were joking or acting or something. I remember trying to cry too but nothing was coming. I think I probably finally did, after a while. But then remember going home and finding my grandmother also crying and so I sat down and wrote my first poem and it was all about April and tears and it all rhymed. I was kind of thrilled.

DA: A stroke of luck changed your life.

AG: Definitely did. When I was 17, my father came home one day clapping and dancing, saying that he’d won the lottery. He was talking about the U.S. Diversity Immigrant Visa he had just won and him being head of household meant that my mother, my brother and I had, too. The U.S. offers this visa annually to residents of countries that have lower immigrant rates in the States. A year later, after all the paperwork had been filed, we flew to Massachusetts. My parents didn’t speak any English when we got here. They were highly educated people who suddenly had to make a living as dishwashers and custodians here and yet they kept doing what they love and know how to do well. My mother has continued to write poetry and my father continues to write critical essays and books on Albanian historical and literary figures.

DA: Your early English lessons paid off.

AG: Well, to some extent. I mean, sure, I was the translator in my family for a while and I had definitely learned the basics of grammar. But I remember struggling my first years in college. I would read the materials, understand individual words but have no clue about the meaning of entire paragraphs. I took ESL classes for a semester. Then regular classes as a business major, kind of following what my parents said was a smart career choice. Then I took advanced comp. and literature electives and knew right away that this was what I wanted to study, forever. I talked it over with my parents and they got convinced. So I switched majors my sophomore year. Becoming an English major is what eventually made me fluent in English. At Atlantic Union College, where I completed my undergraduate studies, I was introduced to Emily Dickinson, Robert Frost, the Transcendentalists, Wallace Stevens, W.B. Yeats. I worked in the school’s library and was in charge of maintaining “The Special Collection Room” which carried numerous works by the best 20th century American poets. I would go in there to dust or add books on the shelves and sometimes couldn’t resist stopping to read a page from Elizabeth Bishop’s letters, or a poem by A. R. Ammons or Louis MacNeice, or to just look, one more time, at a Rupert Brooke photo. I don’t know how to explain that room’s significance to my introduction to American poetry or how it influenced how I started to look at language. I haven’t thought of it in years. Now that I think about it, I never really went after books or poetry. They happened to be available wherever I was. I realize now, because of this conversation with you, how extremely fortunate I’ve been knowing how impossible it was for my parents’ generation to have access to literature, or anything really, in such an abundant and relaxed way.

DA: And then you went to Simmons College

AG: This is really weird. Now that I’m thinking back to all these stages I’ve been through the years, I’m realizing how each one has been profoundly meaningful and crucial to where I am today and why I’ve been able to finally complete this first book of poems. While working on my MA in English at Simmons, I fell in love with the postmodernists (Kundera in particular) and James Joyce and rediscovered Yeats again in David Gullette’s classes. Here, it was David who took an interest in my poetry and although we didn’t have a creative writing class together, he was the first teacher I had to give me feedback on a manuscript as a whole. He could call out bullshit right away and made me aware of what a difference a line break makes. From 2000-2004, I had also been a regular participant in online poetry workshops which were very useful to me. One of those forums in particular, what was then called “the sandbox,” is where I met poets that I’m still in touch with today. That forum has been as important and as meaningful to me as “The Special Collection Room” was at AUC.

DA: You then found yourself in an unexpected place.

AG: I went to teach in Thailand right after Simmons. It was the perfect first teaching job. I worked in both the English and ESL departments at Asia Pacific International University, a Christian school. I taught literature, creative writing and language classes. My students were from all over Southeast Asia, a few from Europe and the Middle East. I lived and worked there for four years. I visited India frequently because my ex-husband is from there. The weather in those countries was overwhelming at times, but it was coupled with the beautiful sounds of geckos and koyals (nightingales) and unbelievably long periods of rain. I didn’t understand this new language, but there were stray dogs everywhere, tuk-tuk drivers, beggars, coolies (the people who’ll carry your luggage at train stations in India), family owned side-of-the-road restaurants and I didn’t need a language to move in and out of these spaces they belonged to. Being in these new landscapes I felt a strong sense that I’d find home anywhere I went and that at the same time, none of these places were for me to own.

DA: Then on to Boston University.

AG: In 2009, I decided I wanted to do an MFA. I only applied to Boston University and, luckily, got in. My experience at BU has humbled me. The program is really small (in my year, there were only 8 poets) and everyone has a unique style and voice. For the first time in my life I was workshopping poems in a group of highly talented people. I felt ambitious at first, then pretty ordinary, then realized that the strengths everyone had were a testament to the high expectations and strengths of the program. I learned a little later into the program that being there with those other 7 poets and our incredibly talented faculty (Robert Pinsky, Louise Glück and Rosanna Warren in poetry), it was never about whose work was better than whose, but about what each of us could learn from one another. Robert often inspired me to really understand this. BU provided, for me, a very comfortable place where I truly thrived in the company of really talented people and where I could finally come back to and focus on my manuscript.

DA: In her introduction to Bread on Running Waters, Rosanna Warren, states, you have turned your adopted language of English “into a subtle instrument, a beautifully judged voicing that never slides into self-pity or melodrama.”

AG: I am deeply honored that Rosanna wrote that introduction. I have read that line many times. I have read it, but I wish I could own it the way you own something you know. English, for me, is a constant reminder of how inadequate I am in public. I never feel comfortable using it unless it’s just me and the page. I sometimes think that I chose to write in this language because this language allows me to be honest and frank in a way that I couldn’t trust Albanian to allow me. For the longest time growing up, Albanian was the language of politicians, harassers, secrets, prejudice, persecutions and people who lied and corrupted left and right. I think I must have subconsciously rejected it when I discovered those 20th century poets whose language spoke to a side of me that constantly felt ambushed on back in Albania.

DA: It’s fitting the first section of your poetry collection is titled “Goodbye Enver Hoxha.”

AG: Yes, thank you for bringing that up. Titling that first section “Goodbye Enver Hoxha” was my way of giving Hoxha and everything he represented to my childhood imagination the same kind of treatment I would give a toy I’d grown weary of. Enver Hoxha, for those first 6-7 years of my life was a kind of toy, a puppet if you will. He was always on TV. Everyone clapped and sang for him. His name was written in big red letters everywhere I looked. Don’t get me wrong, everyone lived under extreme stress and anxiety for many years before and after he died. You only have to think of what the Soviet Union was like under Stalin, to the power of two, to have an idea what it was like in Albania. That kind of anxiety metastasizes and is hereditary through generations I think. But I and all the kids in that first section of my book were children when he died. And childhood is untouched by tyranny and oppression. A child doesn’t understand the death penalty, political prisoners, evictions of families, people controlled by the secret police. I wanted to convey that while he spread terror over the whole land for half a century, that’s all he was to the children – a strange toy we have, unanimously, said goodbye to before any of the adults could.

DA: Tell us a bit about how the long poem “In Her Father’s House” came about?

AG: I wanted to create something of the feel of theater, get the reader to experience a poem like a play. We had been reading King Lear in one of Rosanna Warren’s classes at BU. So I started out by setting up the stage with those berry bushes whispering. I was interested in exploring another complex father-daughter story. I had lost my aunt in 2008. The circumstances around the death of the father in this poem closely reflect the strange circumstances of her death. I just switched the genders of the protagonists and the rest is my best attempt at blurring the lines between genres of writing. I had planned to have all these characters and voices, but it’s mainly a one-woman play.

DA: And today you’re a teacher.

AG: I’ve been teaching since 2003 and can’t imagine something more satisfying or a better place to grow. I teach advanced language and composition classes at Massachusetts International Academy to Chinese high school and college graduates who plan to pursue a higher education in the U.S.

DA: What comes next?

AG: Writing much better poems I hope. Read more widely. Challenge myself. My mother writes in Albanian. I’ve been translating some of her poetry and other Albanian poets off and on. I’d like to make something concrete out of that in a couple of years.