My kid brother Ben pushes the lawnmower across Mom’s overgrown lawn with such vigor that mostly he’s uprooting and not merely trimming the grass. He’s red and flushed, and sweat drips in fat beads down his face. The grass is so tall that he keeps getting stuck and he has to yank the thing back and forth violently, the mower always on the verge of getting away from him as he struggles along behind it.

I lean against the house, shovel in hand, taking a break from dumping good dirt on top of bad dirt so Mom can plant a garden. The pale green paint on the side of the house is blistering in spots. I peel off a few loose patches, crumble them in my hand and let them fall to the ground.

Mom materializes beside me. With the buzz of the mower I didn’t hear the door or her steps. She watches me dust the remaining paint chips off my palm. Her arms cross. She smiles. Her mouth forms the words, “Time to repaint again soon,” but the mower’s too noisy to hear them.

I nod. The last time it was painted I still lived at home and Ben was just a toddler. It’s been well over a decade.

Mom waves down Ben, yelling, “Lunch.”

Can’t tell if he doesn’t see her or just doesn’t care. Can’t see his eyes again because he’s always wearing sunglasses these days. On another pass, he comes right at us like he intends to mow us over, then he veers around us at the last minute and keeps going. I grab Mom’s shoulder and yell in her ear to go in, we’ll be there in a second. She disappears into the house.

I shout Ben’s name half a dozen times but he’s deliberately ignoring me. He doesn’t want to be here. He’s been living with me and avoiding Mom ever since Dad was arrested.

I walk over, grab the back of his shirt with one hand and kill the mower with the other. “Time to go in,” I say, his shirt still balled up in my fist.

He shakes free and yells, “Sure thing, Dad!”

“What did you just say?” I rip the shades off his face and stare right into his dilated pupils.

He steps back looking at the ground and marches inside.

At the table, Mom has prepared a feast. There is macaroni and cheese, chicken breasts, peas, corn, garlic toast, and the list goes on. She’s trying to put her pantry stock to use. The sunglasses have found their way back onto Ben’s face and he sits slouched as low as he can go, steadily shoveling in food and chewing loudly with his mouth open. I rearrange the food on my plate to give the appearance that it’s being worked on. Mom keeps looking back and forth between Ben and I, confused. I fork a singleton noodle into my mouth and work it around a bit.

“So,” she says, “school’s out for the summer? How did finals go?”

Ben doesn’t speak, just keeps chewing loudly.

“Ben’s got credit recovery next year,” I say.

“Oh,” she nods. “Well, I guess with all that’s happened…” she trails off, doesn’t finish.

“What happened?” Ben says between bites.

“Ben, don’t,” I say.

He looks my way, closes his mouth, chews slower for a few seconds and then reverts to his original mode.

Mom keeps looking from my plate to me. “What’s wrong?” she finally asks.

I shake my head, “Just not so hungry.”

Her face wrinkles, “You’re not sick are you? You look so pale.”

Then Ben says, “Jake doesn’t eat food anymore.”

I drop my fork and turn toward him, “Ben.”

“Doesn’t sleep much either,” he continues, “and when he does, he’s always having nightmares and falling out of bed.”

“Ben! Cool it.”

Mom says, “Have you tried Tylenol PM?”

“I’m fine. I’ll be fine.”

Ben says, “No you won’t.”

I sigh and look at him.

“You won’t. We won’t.” His fist grips and ungrips his fork as his knee bobs up and down, his heel tapping the floor. He slams the fork down on the table and stands up, knocking over his chair.

I stand too, grab the back of his shirt in my fist again and say, “Outside. We need to talk.”

He shakes free of my grip and runs out the door. I follow him to the edge of the dirt-filled patch slated to become a garden.

“Take off the shades,” I say.

“No.”

I reach over, rip them off, and throw them over the fence. He crosses his arms and looks to the side.

“What’s your fucking problem today?” I say. “Spill it.”

“Look, I don’t get how you can just sit at the table with her and act like everything’s all normal.”

“You’re mad at her. I get that. We’ve been over this.”

He shakes his head.

“What else? You’ve got more than that, what else?”

He just shakes his head. He won’t look at me.

“Say it,” I tell him.

“What?”

“What you’re dying to say. Say it.”

“It’s just that,” he sighs, and tightly works his jaw around. “You knew. You knew more than anyone. You did. You knew what he was like. You knew what he was doing to me. You even said so in court. You knew the whole time. And what, I’m just supposed to be okay with that, too?”

“No. No you’re not.”

He looks right at me, his face boiling red, his chest rising high and falling hard with each breath. “Why did you let it happen? I don’t get it. Why? You’re no better than Mom.”

I put my arms up and out to the sides and say, “Take it. Take a shot.”

He looks away.

“I’m wide open. Go for it.”

He looks at me, then away, then back, uncrosses his arms and lunges, shoving me with both hands, causing me to step back.

“Oh, fuck it, Ben. You can do better than that.”

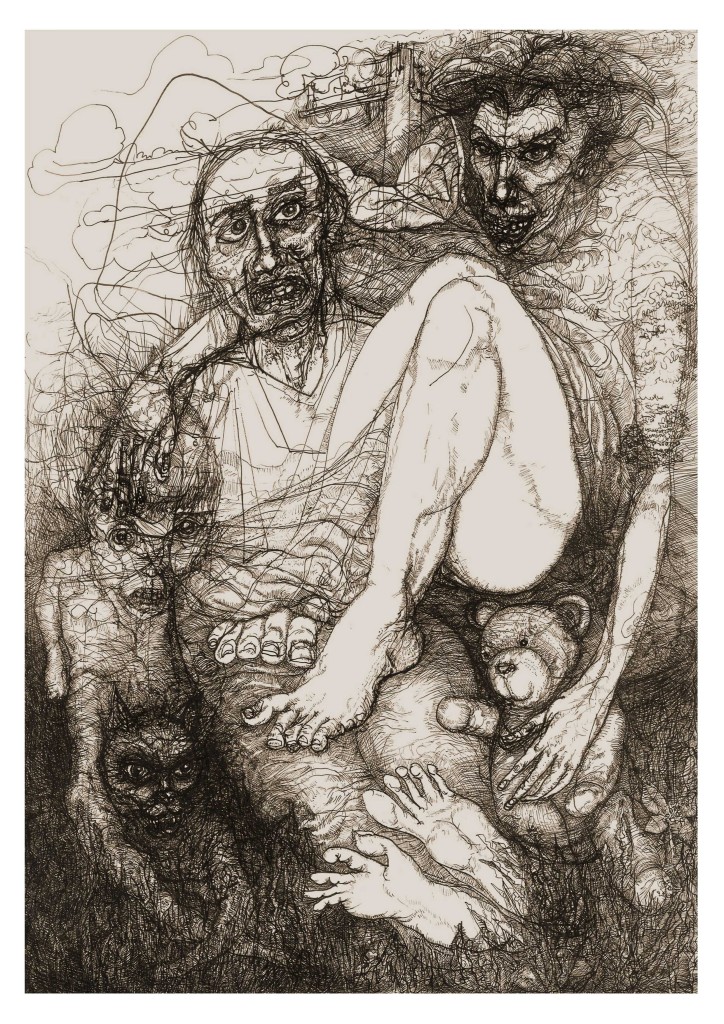

He walks away a few steps. Stops. Turns around and comes at me running, knocking me down into the dirt. He beats my chest with his fists, knees me in the side, pops me in the jaw.

The kid is strong. Enough rage makes anyone strong. Each hit, each impact takes me out of myself just a little bit more and pretty soon I am detached. The soft dirt on my back, the fresh cut grass in the air, the sun up high in the sky. And all I can think about is the last time it happened to me. The last time Dad happened to me. I was twenty. All grown up and not even living at home anymore. It was a camping trip. Dad wanted to take his boys camping. Ben was only five.

Back on his feet, Ben kicks dirt in my face, kicks me in the gut.

Thing is, I only went on that camping trip because of Ben.

He sits back in the dirt, spent, panting, and says, “I hate you. I fucking hate you sometimes.”

I sit up, spit dirt and blood into the grass. “Fair enough.”

“I just don’t get it. How could you not do anything? If you knew, how could you not do anything?”

“There’s a lot you don’t know.”

“Oh, really? Like what?”

I shake my head. “You looking for me to say sorry? Does that word cut it–sorry? And then we can be all happy and you’ll forgive me? Sorry is not what you want. Sorry is not what you need.”

“Then what? What do I need?” he asks.

The whole world goes zing and there’s a ringing in my ears like a mosquito buzzing. “Fuck if I know,” I whisper because my breath is gone.

I remember the smell of Dad’s beer breath, his sweat, and how icy cold his hands were in the tent that night. I remember thinking Ben’s too young. I remember thinking we needed to be really quiet or we would wake the kid up. I remember thinking I’m too old for this. I remember thinking I was supposed to know better.

My eyes burn and everything’s a tunnel, a mile off, unreachable, dizzy. I hate myself. I get to my feet, then double over, vomiting up the sparse contents of my stomach mixed with blood onto the grass. My gut keeps contracting long after I’m coming up dry. Back upright, I stand, swaying, wiping my mouth with the back of my hand.

I remember thinking never again. I remember thinking I didn’t care what happened to the kid, it wasn’t worth it. Ben wasn’t worth it.

Ben says, “You okay?”

“Yeah, fine,” and I hate that word fine. Dad always told me I was fine. That’s why I’m fine. Fine. Fine, I’m leaving the scene now, going into the house, past Mom doing the dishes, down the hall toward my old room.

But I stop.

At the end of the hall, the door to Mom and Dad’s room is ajar and there’s an itch at the back of my head like a memory and I go to the open door to see if it will come to me, the whole time feeling like it’s something I should rather be avoiding. I stand in the doorway, hand on the knob and stare into the room, the disheveled bed and piles of dirty laundry. Mom’s old underwear on the floor, and I can’t be here anymore. I don’t know what I’m looking for anyway. I double back, into my old room and slam the door, kick the bed posts, kick one until it buckles under. Two fists over-head, I land them on the wall that separates my room from Ben’s. And there I stop, slide down the wall as my eyes close, and I melt to the floor because my legs won’t hold me up anymore. I wedge myself into the back corner of the room and curl up, face in my knees, arms bent, elbows at my ears. I can’t breathe right and I feel Dad standing over me.