It was the summer of 1956 in the era of the home bomb shelter. I was nine. I played baseball and fished; and I played war. I dug foxholes at the edge of the garden and flung rocks and apples at bottle-and-can Russian soldiers I set up on the dirt bank across the road. Digging the composted soil kept me in fishing worms, and I told myself that the popping up, throwing hard at the small targets, then ducking back down helped my throwing accuracy.

One day after I’d used up all my worms, I was two feet down into a fresh hole when I realized that if I dug deep enough and wide enough I could collect worms enough to last the rest of summer, and that in the process we’d have a bomb shelter.

With shovel and mattock I dug myself out of sight. Provided you’re alive when you get down there, of course, being in a hole in rich earth is enlivening. The air is moist and smells of growing things. You throw a shovelful skyward and it spreads like water and the sun shines the colors of the rainbow through it.

I’d dug down six feet, deep enough that each shovelful of dirt I threw up left me with half a shovelful in my crew cut. I sat down on the floor of the hole and hunkered back against the dirt wall and was calculating how I’d tunnel under the lawn and into the basement of the house when the sky went dark. I thought it was the shadow of our dog Yogi. But when I looked up he wasn’t there. All I saw was gray sky, the color it is just before dawn, and then the gray turned into tiny shadows I heard fluttering down.

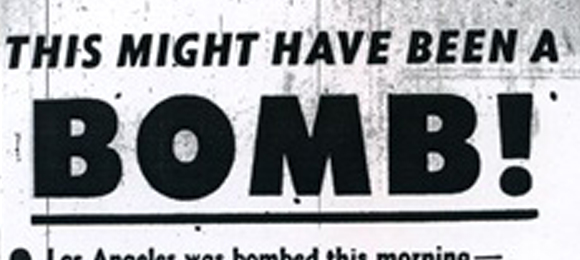

The paper bombs were what I heard. Seven landed in the hole with me. They were black bombs stamped on two-inch-wide white paper strips the length of a legal fish. On the body of the black bomb, in white, was ATOM BOMB, and across the tail fins was THIS COULD BE REAL. In a corner of the white part, in small black letters, was the frequency of the civil defense radio station.

I stacked the seven paper bombs, folded the stack and slid it into the back pocket of my jeans. Then I cut steps up the wall and climbed out.

Hundreds of paper bombs hung in the trees and spotted the grass like flat, little, dead magpies. I grabbed a handful and ran in the house to show Mom.

I banged through the screen door just in time to catch an officer from Fairchild Air Force Base on TV. He was explaining that the paper bombs were part of a Strategic Air Command-Civil Defense exercise. He urged citizens to participate by constructing home bomb shelters or storing food, water and first-aid supplies in their basements.

Mom walked outside with me, carrying my little brother Jesse on her hip, and looked at the paper bombs all around. I ran back in the kitchen and filled two milk jugs with water, then ran back out and stood with Mom and Jesse at the edge of the garden. We turned a circle, and everywhere we looked — on the roof of the house, in the shrubs, in the driveway, all over down around the shop, in the fields and in the pines where the woods began — the paper bombs fluttered in the breeze.

Later in the afternoon I sat in the bomb shelter waiting for my Dad to get home from work and take me fishing. I thought of the paper bombs and wondered if the Air Force would drop more. I looked up through the cool shadow to the blue sky. I lay my head on my arms and closed my eyes and listened for the thunder of a B-52 Stratofortress. I remembered that I hadn’t heard the plane, only the flutter of the bombs. I looked up again and spotted a single tiny thread of cloud, thin as a strand of spider web that could have been the bomber’s vapor trail. Then I remembered we’d need food and first aid besides water. So I climbed out of the hole and ran in the house again and grabbed a box of Vanilla Wafers and a handful of bread sacks and my Cub Scout first-aid kit from my fishing bag that sat with my pole next to the kitchen door. I ducked back down the hole, pulled the paper bombs from my pocket and stuck them between the gauze pads at the bottom of the kit. I’d started stuffing the cookie box into a bread sack to make it waterproof when I heard Dad calling for fishermen.

The Spokane River ran a hundred yards from our house, but my parents wouldn’t let me fish there because it was too swift. So most Friday evenings Dad drove me to Marshall Creek four miles south of Spokane.

All along the path from the road to the creek, through the open fields and woods, we kicked up paper bombs. The wind blew and paper bombs fell from the trees and bushes like big flakes of dry snow. Yogi leapt in the air and twisted like a gigantic white-nosed black trout after a fly, and caught them in his mouth. “They must have dropped a zillion of these goddamned things,” Dad said.

We stopped where the trail sloped down to the little creek. Paper bombs clustered in the willows and birches and floated in the water, backing up against rocks and tree roots, making shadows where fish would hide. In the shade of the trees with the sun behind the hills and the breeze blowing over the water, I felt the same cool sensation on my skin as when I sat in the bomb shelter looking up at the sky.

I dug into the metal box on my belt and pulled out a fat night crawler. A whiff of the dirt on my fingers made me think of the bomb shelter and the paper bombs. “Dad,” I said, “if there’s a war I hope the siren blows when we’re all home.”

“There’s not going to be any war, son,” Dad replied.

I threaded the worm on the single hook of my Colorado Spinner. “But if there is,” I said, “and I’m at school or playing ball, I’ll run home. You don’t come get me — okay?”

“That’s quite a ways,” Dad said.

“I know,” I said. “But I can run it faster than you could drive. All the traffic’s got to go north and you’d have to come south.”

“If the siren blows we’ll be coming to get our boy,” Dad said. “But don’t worry about there being any war, Karl. You worry about base hits. Worry about catchin’ a fish.”

He walked downstream, sat back against a mossy spot in the bank and closed his eyes. Yogi and I fished the dark water that swirled deep in under the roots of a big willow and now and then sucked one of the floating paper bombs out of sight.

I caught a fifteen-inch Rainbow there and two ten-inch Eastern Brook, all on pieces of the same nightcrawler from the bomb shelter.

It was almost dark when we got home. I cleaned the fish at the garden spigot and was hanging the guts on the fence for the crows when Mom called me to dinner.

That night I dreamed the nuke dream for the first time. I’m at school when the siren blows. I don’t know what day it is, but it is not noon Wednesday, so we know it is a real air raid. My stomach falls and I look over at my friend Tom Sears. Tom’s face is white and his eyes are big and his mouth is open. Nobody says anything. We all turn and look at each other. I see the faces clearly: Tom, Pat Henshaw, Janice Fluman. Every mouth hangs open and all eyes are big. All heads turn toward Miss Dicus, and we see that she looks just like us.

I explode into tears and run out the back door of the classroom and across the playground. I pump my legs but they only float. I see Jesse’s face in my mind, all red and contorted like when he’s crying for all he’s worth. But it’s not Jesse’s face, it’s mine. I lower my head and pump my legs and arms, but each step only floats me in the air.

Then I’m out on the highway, standing on the white line. Cars inch past me northward in both lanes. The cars of all the kids in school pass me. Donna Reed and her TV family go by. I grab onto the tailgate of a pickup and pull myself to a sitting position on the bumper. My legs are so heavy it’s like my pants are full of sand. I ride that way in the stream of cars till we reach our road and I jump off and fall into the gravel.

The dream is just like life. The sky is as blue as it is in life, and the clouds are as white and gentle looking, and the gravel stings the palms of my hands exactly as it does in real life so that when I bring my hands up to my face I see little pieces of gravel stuck in them and red indentations where other pieces fell out.

My legs are even heavier now, but our house is in sight and all I want is to make it home before the bomb drops. Living or dying doesn’t matter. All I care about is being with my mother and father and my brother Jesse. With both hands I swing one leg and then the other and move up the road. I can’t see our GMC, but that’s okay because Dad almost always parks behind the house. Yogi isn’t in flight across the field to meet me, but he’s probably inside. They’re all probably inside — my mother, my father, my brother, my dog — all waiting for me in our house.

Then I’m up the steps and in the front door. I yell but no one answers. My legs work okay now, and I run to the kitchen and look out back. But the GMC’s not there. A feeling rises up in me that the bomb’s about to go off. In my mind I see the white flash from the newsreels, then the wind ripping through the clapboard houses, the windows exploding, blowing pellets of glass in slow motion across the Nevada desert. I run down to the basement and into the bathroom where there are no windows. I sit down on the little oval rug and lean back against the toilet bowl. I position my head between my knees and my arms over my head like they teach us in school. I listen for the sound of a door opening upstairs and Mom and Dad calling my name. But the door never opens. And the bomb never blows. The dream ends with no sound and only the darkness and the vacuum feeling of being alone.

I woke up the next morning still scared. I stuck close to Dad till he left for work, then close to Mom and Jesse in the kitchen. She sang little songs to him in his highchair while she made a cake. She held the wooden spoon till he took a lick, then she gave it to me. Jesse burbled like the aquarium at school. I put on the yellow rubber gloves and washed the dishes, then Jesse took his nap and Mom and I watched “I Love Lucy.”

It rained that night. I walked through the grass to the garden the next morning and watched the wet blades leave shiny stripes on the toes of my tennis shoes. In the hole I’d dug as a bomb shelter but hadn’t thought of going to in my dream, I found the cookies damp but edible and the metal first-aid kit with the seven paper bombs in it already rusting. I ate cookies as I filled in the hole and mixed grass clippings with the dirt for the worms to grow fat on.

I dreamed the nuke dream through summer, and I thought of the paper bombs every day. I built models of the B-36, the Flying Wing and the Saber jet — and the missiles Snark and Nike. I followed bomb testing in the South Pacific and Nevada. I wished we’d wiped out the Russians after beating Germany and Japan in World War II. In my rock war with the bottles and cans, after I took care of the Rooskies, I always destroyed China.

The thing that kept the nuke dream alive in me was the air-raid siren. Every Wednesday at noon it howled, and whether I was in town playing baseball or home, my chest emptied. My legs wanted to run, but they were thick and dense and heavy, and I remembered how in the dream I had to lift them with my hands. I asked myself the day and looked around for the time, and I wondered if the Russians were smart enough to strike at noon on a Wednesday so we wouldn’t know the attack was real.

I thought I was finished with the nuke dream when I started high school in September of 1962. But in October the Cuban Missile Crisis scared me so bad I dreamed it every night through Thanksgiving. Something needed to prompt it after that — the movies Fail Safe and On the Beach did.

Then in the summer of 1963 my parents and my little brother were killed in a car wreck and I stopped dreaming the nuke dream.

Yogi and I moved into town with my baseball coach and his wife and I never slept another night in our house. I drove out to the old place that summer and fall. Yogi sat in the seat beside me, and I looked at him and thought how old he’d gotten. I hadn’t paid enough attention to him after I hit my teens and he’d become mostly Jesse’s dog. Yogi was fourteen and most of his teeth had fallen out. The two of us sat in my 1951 Ford on the county road in front of the garden and looked down at the house and the shop and the yard going to seed.

I didn’t get involved much in school that fall and winter, but when spring came and baseball started it helped me live more in the present than in memories. When fishing season opened in late April, Yogi and I hit the creeks on the weekends.

In June, on Coach’s advice, I sold the place to a couple from California. With that money and my father’s insurance and the money from the lawsuit against the man who hit them, I became the richest kid in school.

Yogi and I drove to Nine Mile one day when the California people were gone. Our mailbox was a big old steel thing that Dad had welded in the shape of a house, the name DAVIS running along the roof. I sawed the box off its pole with a hacksaw and took it.

I kept driving out the county road feeling alone in the world except for Yogi lying beside me with his old wet nose on my thigh. That desolate feeling made me think of the nuke dream, and I remembered the paper bombs. I remembered the way Mom carried Jesse on her hip out to see them, and how Dad told me that if the siren blew he and Mom would be coming to get their boy.

I drove till we came to the landfill where the California people took the stuff from the shop that I hadn’t sold at auction. I remembered folding those seven paper bombs and putting them in my first-aid kit, and I was desperate to hold them in my hand again. I knew the old kit had been in a junk box on the storage shelves.

I turned around and parked at the side of the road. I left Yogi in the car so he couldn’t eat anything. I walked through the yellow cheat grass to the dirt and through the mounds of trash till I spotted the old paint cans and petrified paintbrushes I recognized. There were jars of fruit and tomatoes Mom canned that were probably still good, frayed fan belts, seat-less camp stools, a double milk crate full of car generators, a holey navy blue terrycloth seat cover, and an empty can of heavy duty rubbing compound. Then I spotted the blue and gold of my old Cub Scout first-aid kit, which sat upside down in a pitted baby moon hubcap. The top of the kit was rusted through and broke when I pried it with my thumbs. The little bottle of water-purifying tablets, the rubber suction cup and razorblade for snakebites lay in a bed of mold.

I scratched through the layer of spongy white with my thumbnail, but all I hit was the rusty bottom of the kit. The paper bombs had molded away to a fuzzy culture the color of cloud.