Rafaela fainted gorgeously in the hospital when she heard more details about her brother. Her big glossy brown eyes rolled up behind her smooth brown forehead and she wilted like an evanescent white iris flower in her black jeans and thin tank top. Sarcastic old Donald who’d given her the latest info stared at her with horror and admiration, then he felt so much pity for her that he had to turn away violently from her, gritting his teeth.

Her friend Mari who’d come with her on the bus for three hours all the way to Van Nuys Presb from the L.A.C.C. campus let out a shriek, “Rafaela! Ay! Rafaela oh God!” etc. Mari and the other guy from work, Ho, and some other people all dove to catch her, and grabbed her precious arms and almost-bare slender shoulders. But Donald had to turn away in bitter despair.

How could this poor girl suffer such anguish, year after year, these endless crimes against her beauty? he wondered. He was an eccentric, hoarse, fussy Anglo guy in his fifties, a moody bachelor with gray curls down the back of his neck, a failed artist. He was in charge of colors and patterns and prints at the upholstery fabric wholesalers where Rafaela’s ill-starred brother worked as a delivery driver. So oversensitive and insinuating that people thought he was gay, Donald often listened to opera tapes on his headphones – but he wasn’t gay, and the sight of Rafaela fainting bare-shouldered as he spoke to her filled him with a poisoned sense of sexual power which made him want to vomit or hit himself.

He hadn’t seen her for several years until this moment, and she had to be in her early twenties now. He’d noted that she still had that homely round little face with the large nose, and was still lean and lithe though she was an unmarried mother with hordes of overwhelming problems. He met her before when she came to the warehouse once to meet her brother. Her happy-go-lucky jaunty brother was very late that day coming back from a delivery – what the hell had happened to him? The brother was so likable and quick and funny, but everybody guessed he was still using drugs though he tried repeatedly to quit. Rafaela waited and waited, sighing and sighing, till all the warehouse workers were going home and the hot San Fernando Valley sun was blaring in from the west across the parking lots and through the razor-wire fences.

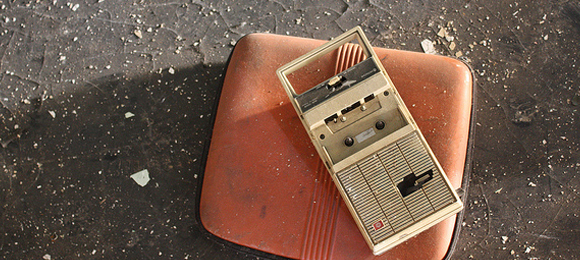

So Donald invited her to wait inside where it was cooler, and she sat at his desk and gasped at the intricate colors and the prettiness of the fabric samples. “Oh look at this one! Ooh, look at the flowers! Oh my God, ay que bonita!” etc. He was finishing up an order, listening to one of his Great Soprano Arias cassette tapes, famous sopranos singing great arias from Lucia di Lammermoor and La forza del destino and all those splendid Italian operas, but he got irritated by her childish squawking and took his headphones off. She sighed, “Oh where is he? Where’s my stupid brother?” She was eighteen at that time.

And she started asking about operas, since she saw the little cassette cases on his desk, and he rambled on pompously. “Of course Verdi is fantastic, but I love bel canto too, Donizetti, Bellini – Bellini is fabulous.” “Oh where is he?” she burst out again and began to cry. She’d come to see her brother for desperately-needed advice, her boyfriend (Anglo, so don’t blame Mexicans), who had already sired a baby in her and wasn’t paying hardly any of the expenses, was now arrested. What in the hell could she do? No, her parents weren’t helping her at all, her alcoholic father had abandoned his family long ago and might well be dead by now, her mother was sick and living with a sister in South-Central, she and the baby were living in El Sereno – or was it El Segundo?

“You poor thing!” said Donald. “You poor baby! Can’t you get food stamps or something?” “I guess so, but I don’t know how, I get so sad, I came here on the bus, all I wanted my stupid brother to do was talk to me – oh there he is!” And her brother finally backed the old van into its stall, then sauntered out into the parking lot grinning and dancing. She ran out to meet him, grabbing for both of his hands and holding them, then they were still talking in the parking lot when Donald drove home.

And her brother still worked there, hanging on to the job for two years, three years, four years, though he was always screwing up. Everybody liked him, he was so witty and so elegant with his baggy uniform shirt, shaved head and tattoos and endless winks and bellowed bits of Mexican song. When he was cheerful, he cast an infectious joy around him, even somber Ho had gotten to like him and of course the secretaries were all in love with him. But he had “low self-esteem” or really something deeper, an inner abyss of self-hatred that he was constantly and instantly stumbling straight into. He’d make a small mistake and shout “Oh, fuck! Oh I am such a fucking idiot!” etc. so anyone who was going to scold him ended up consoling him instead.

He was, he bragged, from solid campesino stock, from the cornfields of Jalisco (or Oaxaca or wherever the hell he said), yet didn’t he have these psychological contradictions worthy of a Dostoevskian Russian or a tormented Spanish royal from Verdi’s Don Carlo? Everybody could see how, when he plunged down from his shiniest happiness, he so frantically craved drugs, whatever drugs he used (cocaine? or pills of some sort?) to dispel the sadness which terrified him so much. Yet he hung on to that job for three, four, almost five years.

Then one time Rafaela called on the phone to talk to him and Donald picked up the line by mistake and said, “What? No, this is Donald, huh? No, he just went out on a delivery, oh is this his sister . . . Rafaela?” “Oh yeah!” she said, “you’re the opera guy!” and absurdly enough, they talked warmly for over a half hour. Her ex-boyfriend was “history” and in jail, her little boy had eye trouble, her mother had recovered somewhat but was mentally ill (it sounded like) and impossible to live with. A friend took care of the baby while Rafaela worked at a fast-food place in Culver City and miraculously even took a class at L.A.C.C.

“Oh, that’s wonderful! Oh I’m so pleased to hear you’re doing so well!” Donald gushed gaily. She demurred, “Well, I’m not really doing so good, I get depressed, I’m always thinking about my baby’s eyes and my father, like what if he’s really alive somewhere?” etc.

And now Rafaela’s brother had been stabbed on a trip to buy some lumber for warehouse shelves, he must’ve stopped off in North Hills to buy drugs because that’s where he was, and he was only supposed to go to the Home Depot in San Fernando and come right back. The call from the hospital came, then a call from LAPD. The boss was furious; one of two short tubby Jewish brothers who owned the place, he was a normally good-natured, talkative man with oddly small anxious eyes, but now he was raving and nearly deranged. He screamed at his “executive secretary” to hurry down to the hospital, then screamed at her not to go at all, declaring that they’d have nothing more to do with Rafaela’s brother who treated them like shit after all they’d done for him. Donald thought the “exec. sec.” better stay to keep a watchful eye on the boss himself, and said, disgusted, “Oh I’ll go! I do every-goddam-thing else around here.” But Donald realized he was too nervous to drive and shouted angrily for Ho to come over here. Then Ho and Donald set out for Van Nuys Presb in the new pick-up truck, leaving Donald’s cell phone number for the exec. sec. to give to Rafaela if she was able to reach her.

“No good, no good,” Ho said very bitterly, shaking his head as he drove – and that was all he said. The trauma of hearing that his young friend had been stabbed seemed to have washed away much of the English he had so laboriously learned. Ho was a sixty-year-old Vietnamese man who had spent years and years in refugee camps, and seemed to have achieved an exhausted calm acceptance of almost anything. But evidently Ho was still as capable of fresh emotion, though in a different way, as fluttery gray-curls Donald himself, who ground his teeth lavishly and cursed and muttered as Ho drove. “Where the hell is this hospital anyway?” Donald demanded. He had a bad head for local geography and already Ho knew the S.F. Valley better than he did.

It was the second or third warm February day in a row and the haze was just starting to come back, but it had a goldish tint and clear winter pastels lingered. The sunlight was still strong and sharp and the San Gabriels were soft dark blue though blurring a little bit. On the broad Valley streets with apartment buildings, smears of bright color from blooming flowers, exquisite white irises and luscious red camellias, showed between the parked cars.

Donald remembered when he took Rafaela’s brother with him on visits to customers, all over L.A. County. In workshops in Compton and Crenshaw, in El Sereno and El Segundo, in San Fernando and San Gabriel, rows of Mexican men in flannel shirts and baseball caps toiled behind chain-link fences, reupholstering cars or sofas or “van-conversions” with fabric Donald had ordered from Taiwan or India. The cars were often parked at random angles with all their doors crazily open while the workers’ fat butts or shaggy heads protruded, waggling to the noise of nail guns. Some stupid problem in batch color mismatches required heartfelt apologies and refunds. Rafaela’s brother acted as interpreter and assistant, then stood around grinning and chatting in Spanish to the workers who, having met him previously during his deliveries, were now all his friends and confidants. It was grotesque to contemplate, and nearly impossible to believe, that some malevolent living man had just today stabbed him with a knife, despite all his smiles and charm and his bawdy shouts of “Ay, ‘mano!”

“Damn,” Donald muttered to himself, his eyes briefly tearing up as Ho drove silently down Burbank Boulevard or one of the other big streets. He thought, poor Rafaela! He wished he’d brought one of his opera tapes, but the new pick-up truck only had a CD player anyway. His cassettes were outmoded and soon would be completely useless. He thought tenderly of Lucia, the Bride of Lammermoor, who was tricked by her brother into abandoning her lover and married someone else. Then her lover came back and denounced her, driving her insane and causing her to kill her husband and herself, leaving her lover to lament gloriously over her grave.

Or What’s-her-name from La forza del destino (Elvira? Leonora?) whose lover accidentally killed her father and then was pursued by her vengeful brother. Yes, she thought she’d finally found peace as a hermitess in that heartbreaking “Pace, pace mio dio” – gorgeous, gorgeous – but then there they are, brother and lover fighting to the death right there next to her cave! Then her electrifying cry of “O, la maledizione!” And, in general, the sexual force of the female voice, the ravishing brilliance controlled, unleashed, shut off – and the men who’d tortured her into song usually standing around and staring aghast at the transcendent magnificence she’d been shattered down into.

Gorgeous, gorgeous, then finally the cell phone rang. “Sweetheart?” he cried pitifully. But it wasn’t Rafaela, it was her friend – Mimi? Mottie? Rafaela was too upset to talk, but they were coming as soon as they could, they had to take the bus to the Valley from L.A.C.C., wherever the hell that was. “Look,” Donald said, almost exasperated somehow, maybe because of the degrading banal details. “Tell her to stay calm, he’s going to be all right. There were only two serious wounds – I don’t know – they just said the knife missed his heart and lungs, it sounds like he’s going to be OK as far as I know. Huh? Ho, what street is the hospital on, did we decide? Is it Sepulveda or Lankershim or what? – what bus line? God only knows, sweetheart, I haven’t taken the bus in thirty years. Just get to the Valley, sweetheart, and it’s on one of those big streets.”

Then they waited at the hospital, he and Ho, and then a friend somebody had called, then also a roommate of the brother showed up. Donald kept drinking sodas, though he detested carbonated drinks and they gave him stomach pains. Ho with his annoying self-discipline refused to have one, so Donald bought him a tiny bottle of water for a dollar and Ho sat cradling it carefully as if it were extremely valuable. Then the cell phone rang and it was Rafaela’s friend.

“Oh, Jesus,” Donald groaned, “well, get here as soon as you can. How is Rafaela doing? Keep an eye on her, for God’s sake.” The friend Mari said Rafaela was feeling dizzy and upset, they hadn’t had time to eat any lunch and now they were stuck in a traffic jam on the bus. A nice lady was letting them use a cell phone but oops, she wanted it back, bye.

“Christ!” Donald moaned. He angrily demanded information from the nurses’ station and acted like an asshole, then sat down again, squeezing the palms of his hands hard into his temples. “Stabbed!” he spat out contemptuously to Ho. “I thought stabbing went out of style, huh Ho? I thought all those cokeheads and knuckle-brains had guns nowadays! Jesus, it’s like something from the 1950s! What is this, West Side Story?” Prospective grief over Rafaela’s brother, the idea that such a joyful unhappy vivid young man could be yanked out of the world in a flash, and that he, Donald, would have to undergo some pain about it, infuriated him. He waited enraged for Rafaela, sick of his pity, increasingly desperate to pass off the burden and misery onto her and escape this hell. Then he realized what he was thinking, and felt ashamed. “That poor girl must be going out of her mind,” he said guiltily to silent Ho. “She hasn’t even had lunch, her baby’s half-blind, she’s stuck on a goddam bus on the 405! Ohhhh . . .”

Then at last the girl herself staggered in, breathless and fearful in her little tank top and black jeans, a magnificent anxiety in her eyes. Her big shambling girlfriend Mari followed her in attendance, a step behind. Donald rose and went to meet her, moved to eloquent but mostly inexpressible emotion.

“Oh, sweetheart!” he said in his low weak sarcastic voice. “You had such a long ride! Didn’t you get anything to eat? Listen, I’m afraid it’s worse than we thought. Some of his organs are all cut up, there’s been so much internal bleeding. He’s still in surgery, it looks pretty bad, they can’t stop the bleeding, they’re trying to patch it all together but God knows –”

Then her lovely eyes slid softly up into her head, she gave a sweet whimper and fainted, breathtakingly sexy and utterly limp. Ho and Mari and the other minor characters rushed to catch her and hold her, the star, tragic heroine and sparkling diva in her mute aria. But Donald could not bear to watch, he turned away violently in unbearable anguish.

He ran away clumsily, fled the general-surgery waiting room and veered toward a window in the lobby which looked out onto a parking lot and a tangle of fences, electrical poles, shrubbery, and sluggish herds of cars. People, and cars full of people, drifted slowly back and forth as the sharp sunlight slanted through the strengthening haze. Donald was filled with anger and awe. He declaimed silently to the people of Los Angeles: oh, you stupid, callous, sullen people, how can you let this happen? What are you doing to these poor beautiful innocent little Mexican-American girls? How can you let this happen, L.A.? How can you make this precious miserable girl suffer so exquisitely that her sorrow blooms in beauty like a stunning red camellia or a great Italian opera?