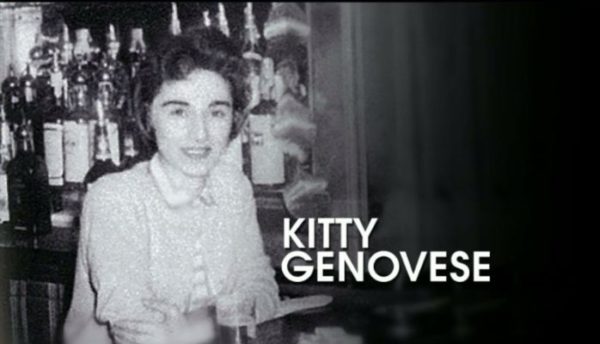

I recently watched a documentary on Kitty Genovese called The Witness. Famous for her murder in the 1960s, Kitty became the poster child for witness apathy. Thirty-eight people bore witness as she was stabbed repeatedly. Despite her screams, no one came. No one rescued her. She died.

The film attempts to unpack this narrative.

The documentary was produced by one of her surviving brothers, Bill, who was also its subject. What must it feel like to not only lose a sister but to have the whole world continue to scrutinize her death decades later?

Kitty died in 1964 at age 28. Her death is still a topic of debate half a century after the fact.

What is that like for her family? The ones left behind. The ones that were left to carry the pieces. They never asked for this burden. And they will never be unencumbered.

The death of a child, even once she’s reached adulthood, in many ways destroys a family. Lives continue, as they must. Time can’t be reversed. Happiness, complex previously, becomes more so.

Bills must be paid, pets fed, plants watered. Life’s minutiae don’t cease despite the impossibility of circumstances. You continue performing these rote tasks while contemplating the point. Why are we here? Why do we continue? Why do we persist in this futility?

Kitty’s family had to move forward. They lost Kitty. Shortly after, Vincent, her father, suffered a heart attack. Bill, her brother, went to war, Vietnam. He lost both his legs.

There’s no cap on tragedy. It’s not a finite quantity. Just because Kitty had died didn’t mean the rest of the Genovese family was spared further hardship. It didn’t mean that bad things ceased happening. There was no force that declared “enough” and made it so.

Kitty’s mother found God. That was her consolation, I suppose. She inserted a higher power into what were otherwise irreconcilable circumstances. People often find God in grief or grief in God; I don’t know which.

This always confused me. If there is one godless place in this world, isn’t it tragedy? Why would God have let Kitty die? Why would God have created her killer Winston Mosley? Why would God have saddled her family with this impossible burden?

I don’t know the answers to these questions. Even if they exist they aren’t clear-cut. Maybe I’m missing something.

When my sister Georgia died my dad started attending church. He is a devout atheist. That hasn’t changed.

It’s the same church where her funeral was held. Presumably, he sits in the same pews he sat in on that day. I don’t know; I’ve never been. I don’t want to. I’m still angry.

He must take up the same space as when he waited for his name to be called on that warm May day. Time for the eulogy.

I avoid asking questions. Questions about this anyway. Questions make people sad. Questions make people remember. They can no longer pretend.

I think he goes to feel closer to a small piece of Georgia. Maybe by coming to the location of her final testament, he can stand in the chasm that exists between life and death. Not purgatory, not heaven, not hell, but somewhere in between. Maybe it is in this space that he connects with her, feels her presence, can speak to her freely. Maybe here Georgia isn’t dead. Maybe here he can breathe unhindered.

I’ve tried asking him about it. The conversation ends before it begins. I try to play the witty jokester as compensation. I’m perpetually upbeat. I try in vain to stop the spiral.

According to Bill, Kitty’s parents were never truly happy again.

Winston Mosley died in 2016, not long after being denied bail for the 18th time just the previous year. Kitty’s killer is gone. Does this change things? Does this make the loss easier to bear? Is this justice?

In the documentary, Bill reached out to Mosley seeking some semblance of closure. He refused. He blamed Kitty’s death on someone else. Was he crazy before he went to prison or had a half-century institutionalized made him so?

After Kitty died, her family stopped saying her name. The children of Kitty’s siblings knew almost nothing about her life. They read more about her in school texts than they heard from their uncles and aunts.

This happens when the circumstances of death are particularly tragic. It becomes easy for that person’s existence to be conflated with the method of death. That comes to define them. It becomes the piece that constitutes the whole.

Kitty was married and divorced. She worked at a bar. She went to jail briefly. She lived with a female partner. What must this loss have been like for the woman she loved? How did she express her grief? Ultimately, how do any of us?

I’d thought a lot about this recently, the erasing of life with the arrival of death. Both my parents have erected shrines to Georgia in their homes. I look out the door of the bedroom I’m currently in and see her old room. The place she died. It has been left intact. From the doorway, I can see her ashes and the butterfly-covered urn that she has been interned to. Casting my eyes downward I see a pair of velvet Doc Martens. I saw a stranger wearing the same pair on the train. It hadn’t occurred to me that there was a second pair. The same pair she wore at her viewing.

Her body was composed, dressed, made up, prepared for the family to have a final moment. I remember I had touched the moth tattoo on her arm and quickly withdrew. She felt waxy, dead, not human. It finally hit me.

After the viewing and then the funeral, she was cremated. Before she turned from body to ashes, her shoes were removed at my dad’s behest. He wanted to keep them. She had asked for them as a present, carefully sourced them somewhere on the internet. They now stood next to several other pairs, belying their own significance.

So there she was, those ashes and those shoes. That was it. All that was left.

I live in a family where few words are verboten. The word Georgia, though, has come to be the most loaded. It’s the word that silences the room. People look down. They find an excuse to change the topic. People have stopped saying her name.

My siblings and I whisper it to each other out of our parents’ earshot. We’re broken, but not like they are. We want to protect them.

But why do we stop talking? She was more than the way she died. She was more than those final moments. She did good things. She did bad things. She was human before she wasn’t. Alive before she was dead.

Kitty Genovese, photographed in her grandparent’s backyard (Brooklyn, NY, 1959)

It must be bizarre for the nieces and nephews of Kitty to have grown up knowing that they were related to her. This person whose death was never discussed in the home, only read about in the media. It seems a disservice to Kitty’s memory.

Kitty was close to her siblings. Her relationships with them were important both to her and her brothers and sister. Was it difficult to stop talking about her?

There’s something to be said for suppressing feelings, moving forward, forgetting. The dead get to be dead. We can’t. They’re gone. We stayed.

And as long as we’re alive we have to figure out a way to navigate. Nevertheless, we continue to carry pieces of the dead with us. Some days they are smaller than others, but they’re always there.

There certainly won’t be a day that I go without thinking of Georgia. Sometimes an hour passes and I realize her name hasn’t come up in my head. That’s about the longest.

I’ve learned to live with that voice, those thoughts. I’ve learned to stop them from getting too loud. I don’t let them drown out everything else. Mostly they’re a whisper. I consciously keep the volume down.

The voices are always screaming in my dad’s head. I can tell just by looking in his eyes.

But it’s still early days relatively. Maybe things will change. Maybe my dad will figure out how to survive in a world that she is no longer a part of.

I thought of Joan Didion who said, “a single person is missing for you, and the whole world is empty.”

My dad understands this acutely, viscerally.

I guess we can only hope that the rest of us can come to be enough. We must hope that the love we give stops my dad from drowning. At this point his eyes, mouth and nose seem barely to breach the surface of the water. With time maybe his whole face will emerge, then his neck, his torso, his legs, his feet. Maybe one day he won’t even feel the water at all. Although I doubt that.

But that’s OK. Sensing Georgia, carrying her now is his version of the afterlife. There may be no heaven, but there is this life and we can all try and carry the best pieces of her with us. That’s our way of honoring her, remembering her, keeping a piece of her alive.

That’s the best we can do. Maybe that’s why Bill Genovese made the documentary about his sister. He shared her life before her death. He told the world she was a person before she was the victim of a crime.

There’s one beautiful scene towards the end of the film. Bill enlists a surrogate who reenacts that night. She screams the words Kitty screamed on the street Kitty screamed them in the early hours of March 13, 1964. She makes the movements Kitty made. She starts at the sight of the first attack from Mosley before staggering to that of the second. The second place. The place where Mosley returned half an hour later and finished what he had started.

No one’s lights turned on. No police came. No one responded to the screams of the surrogate. This could have broken Bill, but it didn’t. He hugged the woman who stood in lieu of his sister when she couldn’t. He cried. I cried. I wondered if this brought him some sliver of peace. Did it help him reconcile the choices that he had made in the wake of Kitty’s death, because of Kitty’s death, despite Kitty’s death? Would he have made them if she hadn’t died? Does it matter?

He carries Kitty with him as I carry Georgia with me. He made The Witness as a love letter to his sister. He shared her life. In that way, he made her immortal.