I tried hard to create a book that would be the same as an experience in a classroom, and that’s really fitting to what I feel is essential: accessibility and dialogue.

Tawnya Selene Renelle

This June, I had an inspiring Zoom meeting with an extraordinary poet I met during my MFA program at Goddard College, who presents herself as an accidental memoirist or someone who works within nontraditional memoir mediums. She is a “body writer,” a master of embodied, corporeal poetry, and soon to be a doctor of creative writing focusing on Experiencing the Experiment of Creative Writing. She is an amazing and brave performer who organizes sex-positive poetry nights, giving her audience permission to talk and write about their lives, and a teacher of writing who will challenge you to try what you haven’t dared trying before. Tawnya Selene Renelle, experimental writer and creative writing educator from Bellingham, Washington in the USA. She currently lives in Glasgow, Scotland where she is steps away from completing her DFA in Creative Writing at the University of Glasgow.

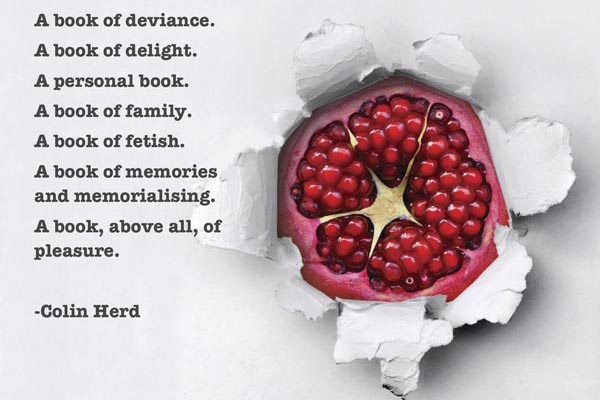

In the following interview, you can read about Renelle’s debut poetry collection This Exquisite Corpse, about her academic experiences and experiments, and about her mission of helping others put their bodies on the page.

Right from the title, This Exquisite Corpse, to its last line (I am passing because I am fat), I was always inside of a body – yours or mine. I’ve known you since you started writing the snippets of this book, and it seems to me today that you hadn’t known back then how corporeal this collection would become. When and how did you acknowledge your literary strengths, and when did you first see your path toward becoming a “body” writer?

I think this knowledge probably came in the process of putting the poems together. It wasn’t a thread that I was always aware of and not until I had laid all the poems in front of me to figure out how to structure them into one book. I actually viewed the collection itself as one poem in addition to having those individual poems, so the titles are very intentional, and so is the order of poems.

I hadn’t really considered myself a body writer, but now I do. Everything I write is embodied. It’s really hard to escape. My entire DFA thesis is situated in the body as well, and besides, I wrote in an entire chapter about the body and how to present the body in writing. Writing the body is important, but we often forget it. Writers can be very cerebral, trapped inside our brains while imagining things and using language and thinking of all the different ways of getting words on the page. But our bodies have their own experiences with the physical world, which inspires a lot of writing. So now I help people tap into that.

I’m glad that my collection is so embodied. I think this is how and why people connect to it – they feel like they now have permission for their own bodily experiences.

This Exquisite Corpse covers everything that a body can experience from the conception (the poem Alive) and even pre-conception to birth and experiences of all senses, then delight, pleasure, physical pain, and later experience of loss and physical disappearance or the transformation into the ashes following the deaths of your friends.

How hard was it for you as a poet and a memoirist to write this collection, continually revisiting the places of pain and again, returning to grief during the revisions or later, during your book tour performances?

It was difficult. I came into my graduate program at Goddard, expecting to write one thing, and then, I started writing something completely different. Initially, I wrote a poem about time. I wrote about the passing of 365 days from the day she died until the anniversary. I showed that poem to Beatrix Gates, my advisor, and she said, “This is it. This is the experience about which you’ve come here to write.”

Some poems were more challenging to write, but, in the end, it was quite cathartic to process. My path to graduate school was really prompted by the death of my friend and by that grief and loss and realizing how short life is and how unpredictable it is. The pain became the impetus to doing what I wanted in life, so in ways, I feel like my poems honored my friend.

What happens when you perform? Are there evenings when you decide to not read about grief?

It really depends on the performance I am doing, so now, when I read the grief or the death poems, I can read them in a more detached way because I recognize that I am going to present an experience that my audience can relate to. I feel a sense of purpose when I read them. I listened to my audience react: people come up to me and say, “I know someone who’s addicted to heroin,” or “I know someone who committed suicide,” and it gives a sort of permission for the person who’s heard the poems to talk about their experiences, too.

But, now I have a whole subproject that is related to sex poems. I didn’t think I would ever be a sex-positive poet and develop a mass platform for that, but I am doing it. I am hosting events called “Fucking Filthy” (I’m not sure how you will write this in the magazine) that are sex-positive evenings with some different guest performers. They culminate in the reading of lists the audience is writing.

I was lucky to experience your sex-positive performances or artistic sexplorations. What I knew back then when you were starting this is that there is something so magnetic and trustworthy about you. You stand tall and read, and suddenly, the audience receives permission to express themselves, too. You put your body out on the page, and the audience responds with incredible courage. Would you say that you’ve been on a secret mission of giving others permission?

I spent three years doing my Ph.D. while performing and publishing a poetry book and touring after the publication, and also teaching. The number one thread I found in anybody willing to listen to me is that they just want permission. Everyone I’ve met in the world was walking around with an enormous weight on their shoulders. Sometimes it’s trauma, sometimes it’s something beautiful, and they are just seeking someone to say: “It’s okay.” “You can talk about it.” “You can write about it.” “You can tell me about it.”

And so, I have realized that if I get to be the person who gives people permission, it is the biggest privilege and honor in the world.

I talk, I teach, I read poetry to people. All of a sudden, they feel liberated to live their life and talk about their experience. It is the best thing, the greatest gift I found.

The essence of the work you had set off to do when enrolling in our MFA program at Goddard College was to challenge yourself and the norms. To experiment and embrace the experience of your body in this world. After you’d graduated with the MFA, you switched continents and began a Ph.D. program at the University of Glasgow. Some (or many) writers believe that academia is restrictive, yet you’ve experienced a new liberation through working on your Ph.D. Can you explain this experience?

I think this is a huge misconception about doing a Ph.D. Yes, doing a Ph.D. narrows your focus. When you are applying, you have to have a clear focus on the project you want to do, but it’s certainly didn’t restrict me. Doing my Ph.D. opened up the world to me, but that, in large part, has to do with the program I chose. There are some programs in the UK specifically where everything is really traditional, and those programs wouldn’t have worked for me, they wouldn’t have let me push into the boundaries and spaces of what I consider Creative writing. However, I was fortunate that my program gave space for that, that my program supports those challenges and supports this kind of crossover of creative and critical writing, and sees that the two can sit side by side.

And it has been the most liberating. I started my MFA, knowing I wanted to get a Ph.D. It was always the path.

In September, I will be a doctor, and a new door that is now opening to me is big. There are lots of opportunities such as teaching fellowships or post-doc for further research. There are lecturer positions. And the networking that opens up to an inspiring community.

With your poetry, you found a way to start an honest conversation with the audience. Is that what you are trying to do with your creative writing workshops, too?

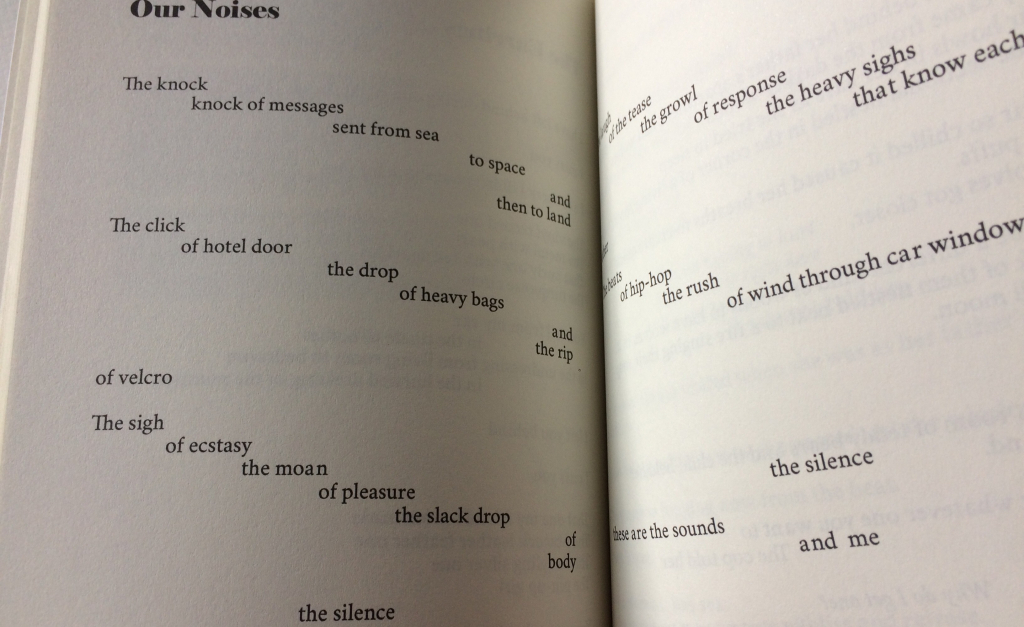

100% so. To explain my workshops, I have to tell you about my thesis. My Ph.D. thesis is a textbook, and I call it a textbook out of extreme stubbornness because I think we should question what textbook means. It is a mix of memoir, poetry, critical analysis, critical theory, art. It does weird things on the page. It has “choose your own adventure” style footnotes that allow the reader to move between all eight of the chapters. And it has blank space. I ask the reader questions, I offer prompts, and I give them space to write into the text.

I tried hard to create a book that would be the same as an experience in a classroom, and that’s really fitting to what I feel is essential: accessibility and dialogue. I created the text that really provides that space and mirrors everything I do in the classroom.

The workshop is all about asking people to consider things they haven’t before and give them permission to experiment, play, and have fun. Sometimes I feel like I’m the first person who tells writers, “You don’t have to do it that way,” “You don’t have to write a novel that looks like a Charles Dickens novel,” “How do you want to write? How does your story need to be told?”

And you call this Experiencing the Experiment of Creative Writing. Which, again, gets us back to the body story.

Yes.

This Exquisite Corpse, besides the strong sense of the body, offers a great sense of place. While reading the poems, the audience can easily experience the Pacific Northwest. Can we see the place in your new book? Can we see Scotland, the country that you fell in love with?

Yes. I think so because in ways I’m like an accidental memoirist. Or I am a memoirist who works within nontraditional memoir mediums. So, the textbook is a recording of my experience of moving to Scotland from America. There is a lot about the Highlands, about my ex-boyfriend, because I wrote a large portion of the book while we were living together, and there are parts of the places we visited on our travels.

People learn through stories – through someone’s lived experience. And through talking about someone’s lived experience, they can tap into history, social justice, and all sorts of different topics.

The memoir I used in the textbook is about giving the reader the access point to the information and knowledge that I am trying to share with them.

The place becomes the grounding, the proof that I am a human as well and that the reader can connect to me and through me, the material.

What is the project that keeps you occupied during the social distancing time?

I am writing a fictional account of a love triangle, and I’m using Anais Nin’s book Henry and June as my intro into the text. I use three fictionalized narrative voices, the original text and the quotes from both Nin and Miller. It’s an exciting project – there are not many literary texts about triangles. It’s also queer, plus, it will give people access to Anais Nin’s and Henry Miller’s life and work – another important dimension.

If you are interested in Experiencing the Experiment of Creative Writing and trying what you haven’t tried before, consider enrolling in Tawnya’s next nine-session workshop starting on July 5th via Zoom exploring Hybrid and Experimental Forms. Through different themes, each week, writers will investigate and experiment with form and genre. Each session will offer writing exercises to stretch the imagination and page of your writing.

For our readers, Renelle is offering a 20 percent discount if you email her with the code Pif Magazine. All the information is available on https://tawnyarenelle.wordpress.com/experimental-writing-course/

instagram:tawnyarenelle

twitter: @trenellepoetry