In the 1920’s and 30’s, Hemingway, James Joyce, Ezra Pound and a host of other aspirants went to Paris to live the good life, write and find fame. This tatty group of pseuds, braggarts and bar-flies managed to turn out, in between heavy bouts of drinking, sex, and bickering amongst themselves, a good stack of the twentieth century’s literary masterpieces.

Many of these masterpices were talked about, written, or corrected in a handful of Paris cafes where the literatti and expatriates spent most of their waking lives and a good part of their sleeping lives.

Paris, at the time, was swamped with budding geniuses . Young men and women who had a remarkable confidence in their own talents and who developed circle of mutual admiration in which to foster their works.

Cafes were the perfect places for them to meet; warm, cheap and full of other like-minded prodigies.

Unsurprisingly, their biographers have transformed these ordinary Parisian cafes into furnaces of literary creation where the writer-heroes beat out the great modernist themes of the twentieth century. But if we believe the writers themselves, cafe life was often dead boring. Long periods spent sitting over a coffee to avoid going back to freezing lodgings in gloomy parisian boarding houses. If other writers were with you, the closest you’d get to intelligent conversation might be a few acid remarks about Gertrude Stein’s love life or Ford Maddox Ford’s bad breath. To break the monotony of not writing and while you waited for Inspiration to arrive , you’d get blind drunk; as great writers do.

All of the cafes are in Montparnasse and St.Germain, within easy walking or staggering distance of each other. Surprisingly, they are nearly all still open. Most of them are now outrageously expensive and have been refurbished in dazzling laminates, veneers and strips of shiny brass. Far from being the gathering places of artistic outlaws, they are full of tourists and snotty, over-preened Parisiens. Their waiters are known for their arrogance and are masters of the art of confusing foreigners with the French Franc Shuffle, an advanced technique for short changing.

At the Deux Magots, one of the most written about of the well-penned cafes, I asked the waiter if writers still frequented the cafe. ‘Les ecrivains?’ he sneered, waving his hand dismissively over his clientele. This was his reply to what he clearly thought of as a very stupid question . Looking over the carte it was easy to see why. Only writers in the ‘big advance’ league could afford to sit here.

I ordered a beer ($6.00) and a designer-small tarte aux fraise ($9.00) and wondered what Hemingway would think if he was sitting here today. Probably give him good reason to commit suicide all over again.

But was it always like that? As I slowly sipped my beer and put small forkfulls of the tarte aux fraise in my mouth I asked myself how much the price increases since the 30’s could be attributed to inflation and how much to good old Parisien avarice.

According to Hemingway, if I’d been in Paris sixty years earlier the cost of my tarte and beer would have bought me a weeks hotel accomodation for two and three course meals with wine every night.

By the time that I’d visited all of the cafes I’d spent enough money to have been able to live in Paris for the whole of 1931, eat five course meals every night, drown myself in champagne and throw a weekly party for less fortunate literary friends like Hemingway and James Joyce.

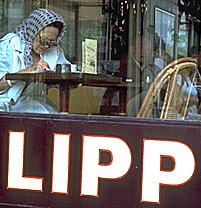

After paying for my elegant little lunch which included a 15% compulsory tip for imaginary service, I crossed the road to the Brasserie Lipp, another famous ex-patriates haunt .

The Lipp hasn’t come along quite as well as the Deux Magots. Its ugly enclosed glass and aluminium terrace is in need of a face lift, even a good clean would help, while the interior has obviously been left to moulder away for decades. The Lipp’s clientele, at least when I was there, had none of the flash and fashion of the Deux Magots. There was a sickly looking man sitting alone and brooding over his coffee, a full ashtray of Gaulois stubbs smouldered in front of him as he prepared another between yellowed fingers. He didn’t raise his head once. Didn’t bother with the rest of us or the people passing on the pavement. Very un-cafe style. Cafes are places where you spend your time twisting your neck around to see and make sure that you’re seen. His form was abysmal. Then there was me, a small coffee. And in the far corner; an old woman bent over a crossword with a dirty poodle thing at her feet scratching its sores.

In a chapter titled, ‘Hunger was a good discipline’, from the autobiographical, A Moveable Feast , Hemingway describes an undisciplined visit to the Lipp. Here the hungry young artist living on the knife edge of starvation put away more than a litre of beer, two plates of potato salad, a heavy sausage with mustard sauce and a quantity of bread soaked in olive oil. Presumably, all for the price of my expresso and a few days of indigestion. If you’re feeling particularly gluttonous you can order a duplicate of Hem’s meal for about $30.00. Belch.

Unlike the Deux Magots where the waiters hustle their customers out of their seats as soon as they’ve finished, I had the feeling that I could have sipped my coffee at Lipps until late into the night. But when the poodle thing started breaking wind, I paid up and headed for the Boulevard du Montparnasse.

Around the intersection of the Boulevard du Montparnasse and the Boulevard Raspail there is a concentration of cafes made famous in the 20’s and the 30’s: The Select, the Dome, the Rotonde and the Coupole . This is where Hemingway said ‘ the scum of Greenwich Village, New York, has been skimmed off and deposited in large ladle fulls’, where ‘ you can find anything you are looking for… except serious artists…’. Of course, Hem himself had arrived in one of these ladle fulls but was, hic, ‘serious’ and therefore able to mix freely with the ‘scum’ without becoming an object of his own satire.

The Select is now a glitzy brass and glass cafe with an expensive terrace, a silk suited manager looking like a fugitive embezzeler and a clientele that equals the Deux Magot’s for its mix of pretentiousness (the Parisiens ) and self-conciousness (the tourists). Glass of wine – $7.00, warm goat’s cheese salad – $11.00. Served with the right quantity of sneering and rudeness from the waiter.

The Select was founded by Monsieur and Madame Select (if you can believe that name), neither of whom would probably be allowed into the place today. John Glassco described Madame Select as having ‘high colour, shrewd eyes, and a bosom like a shelf… she wore little black fingerless mittens that kept her hands warm without preventing her from counting the centimes’. Monsieur Select ‘ who made the Welsh rarebits on a little stove behind the bar, had long melancholy moustaches like Flaubert’s’. These days the only place that looks vaguely cafe-arty in the Select is the back room that you pass through to get to the toilet. The walls of this little chamber are covered with posters advertising art exhibitions. Although the terrace was crowded and people were lining up to get seats, only a dejected looking loner sat hunched in a corner of the back room nursing a glass of wine. Could this have been what it was like then ? It felt a lot closer to it than did life on the shiny, over-priced terrace. Either way, I didn’t stick around. I had more cafes to visit. My capacity for dissappointment hadn’t been completely exhausted.

Across the road from the Select is the most famous cafe of them all, the Dome. Before World War 1 the Dome was a rundown little bar, small and ugly. It was the hangout of Lenin, Trotsky and their fellow revolutionaries. Now, it is huge and ugly and the hangout of bankers, conservative politicians and, yes we’re everywhere, tourists. In 1923 the Dome was enlarged, refurbished and jazzified. Lenin and Trotsky left and the expatriate writers and artists arrived. This is where the Nobel prize winning writer, Sinclair Lewis, was told to shut up by the resident ‘serious’ artists because he ‘was just a best seller’, and where Pascin, the French painter, offered Hemingway one of his beautiful young models to ‘bang’. Hemingway refused and headed home to his wife, remembering the jokey Pascin in his autobiography as one whose ‘seeds are covered with a better soil and with a higher grade of manure’. Yes, I’m afraid these are the stories that have made these cafes meccas of literary pilgrimage.

Today, the Dome has become a pricy cafe-restaurant specialising in seafood. It’s open air seafood bar is staffed by a group of overworked and underpaid immigrants who are more likely to have heard of Lenin than James Joyce.

The interior is all art deco : mirrors, marble and tableau curtains and, of course, lots of shiny brass. I had a dozen oysters ($ 24.00 ) and a glass of Sancerre ( $6.00). Hemingway ate oysters and drank Sancerre, maybe at the Dome, after finishing one of his stories. He was feeling ’empty and both sad and happy’ as though he ‘had made love’. The succulence of the oysters and the crispness of the wine had the effect of bringing him out of his post-partum depression. I, on the other hand, was wondering as each succulent oyster slid down to meet the Deux Magots tarte and the Select’s chevre salade, if this story would ever earn back the money I was investing in it. I plunged into pre-partum depression.

Opposite the Dome is the Rotonde. This is where Malcolm Cowley, the American writer, became a favorite of the Dadaists for beating up the Rotonde’s owner. The owner was suspected of being an informer who reported Lenin’s conversations to the police. Reason enough to beat him up. Besides he had ‘the look of a dog caught stealing chickens’. Cowley and the famous Dadaists, Tristan Tzara and Louis Aragon, confronted the man and Cowley whacked him on the jaw. All good clean fun. Later, as Cowley passed the restaurant he was arrested by a couple of gendarmes and given a good beating himself. After the incident Cowley was transformed into a leading European Dadaist writer, in spite of his writing having nothing in common with dadaism. That’s how easy it was to become a famous writer in those days.

I had another coffee at the Rotonde. After three or four of these cafes the confusion sets in. They all start looking the same, smelling the same, the waiters are all the same, the clients are the same, the prices are the same. Only the Lipp stood out for its lack of clients and its fatigued look. Yet the Rotonde must have been different enough in the days of Trotsky and Lenin. When they fled the bourgeoisification of the Dome by the corrupt American artists, they simply crossed the boulevard and set up camp with their Bolshevik friends at the Rotonde. Today the Rotonde is a shade down-market from the Dome but, like the Dome, both Bolsheviks and corrupt artists have moved on to leave space for the rest of us.

Crossing the boulevard again, I went to the Coupole for dinner. Henry Miller used to be a regular at the Coupole. And it was right here, against the same bar that I am leaning on, perhaps this exact spot, that he used to electrify other regulars with his theory that prostitutes were the only pure beings in a world of reeking garbage. Heady stuff.

The Coupole is a vast, cavernous place, with seating for hundreds. It also specialises in seafood and has a seafood bar staffed by enterprising immigrants who insisted that I give them 100 francs each to photograph them. Sitting in the huge, well lit dining room is a bit disconcerting. If you want a spot from which to observe without being observed, forget it, there’s a spotlight on you wherever you are. But the Coupole’s food still makes it one of the Paris cafes worth visiting. I had a salade riche au fois gras ($20.00) , half a bottle of Pouilly Fume ($25.00) and a gratin de fruits rouges ($10.00). A great meal but the cafe has all of the charm of a busy railway station.

After the Coupole, a walk up the Boulevard du Montparnasse to the Closerie des Lilas.

The Closerie des Lilas has claims to being the birthplace of the Surrealist movement. It was here that Andre Breton, Eric Satie, Ferdinand Leger, Picasso, Matisse, Brancusi, Cocteau and about a hundred others held the Modernism Congress in 1922. Tristan Tzara and his Dadaists were invited but refused to have any part in the meeting. Breton, good friend of Tzara’s, was accused of sabotaging the meeting by deliberately antagonising the Dadaists. Doing what any sensible genius would do, Breton broke away from both the Modernists and the Dadaists and set up his own movement, the Surrealists. If you think this all sounds like schoolboy gangs fighting over space in the playground, just remember it all started at the Closerie des Lilas.

The Lilas’ cashier, a plump old matron, was watching ‘Dallas’ in her little cubicle when I approached her to ask about the ‘good old days’. Well, she was pleasant enough, even genteel, but she obviously knew little about the famous personalities that had made history in her cafe. She was only interested to know if I’d ever been to Dallas and if it was really like it is on the tele. The Surrealists would have liked her.

There was only one more cafe that I wanted to visit, the Cafe du Depart on the rue Gay Lussac. This was Beckett’s ‘local’. He used to sit here for hours without saying anything, just steadily drinking. At the end of these periods he would come out with a gem of cafe-philosophy.

One of these was ‘Sunshine is an overrated virtue’. Bet you couldn’t have thought of that. There’s no chance that you’d be able to gestate one of these gems in the Depart now. The noise of the pinball machines, radio and shrieking teenagers kills all thought, let alone creative thought.

Unlike the other cafes, the Depart has not gone up in the world. It is a ‘caf’ – formica tables, mirror-tiles on the walls, plastic chairs and filth on the floor. You can even get an English breakfast there; cornies, bacon’n’eggs, n’tea. Not a place to wait for Godot or anyone else.

At the end of a long day tracking down the cafes where literary legends were born I was able to produce, with a little inspiration from Beckett, my own bit of cafe-philosophy : Writers’ cafes in Paris are an overpriced virtue.